What is Git really?

I have been using Git for many years. But honestly, I have no idea how it works, let alone what it actually is. And I stumbled across an extremely good Git explanation video that makes me want to tear Git apart and understand what every command does, not just casting Git magic spells. I am not only going to write about Git commands, but also about how those commands work. So having some basic knowledge will help a lot in reading this blog.

Data Structure of Git

- Git is a tree, a one-way family tree. [¹](#Lies that I made)

- Commits are snapshots of the project.

- Branches are pointers to a commit.

- HEAD is the pointer we are looking at.

Git init

Let's git init and explain everything on the way.

> git init

Initialized empty Git repository in C:/blabla/.git/

It creates a bunch of files in .git, and this initializes a Git repo.

.

└── .git

├── HEAD # <--- This is our HEAD pointer

├── config

├── description

├── hooks

│ ├── [truncated...]

├── info

│ └── exclude

├── objects

│ ├── info

│ └── pack

└── refs

├── heads

└── tags

10 directories, 18 files

The HEAD file is our pointer, and the content ref:refs/heads/main means we are on the main branch.

> cat .git/HEAD

ref: refs/heads/main

First commit

Let's work on our repo, and submit our first commit.

> touch HelloGit.txt

> git add HelloGit.txt

> git commit

> ...

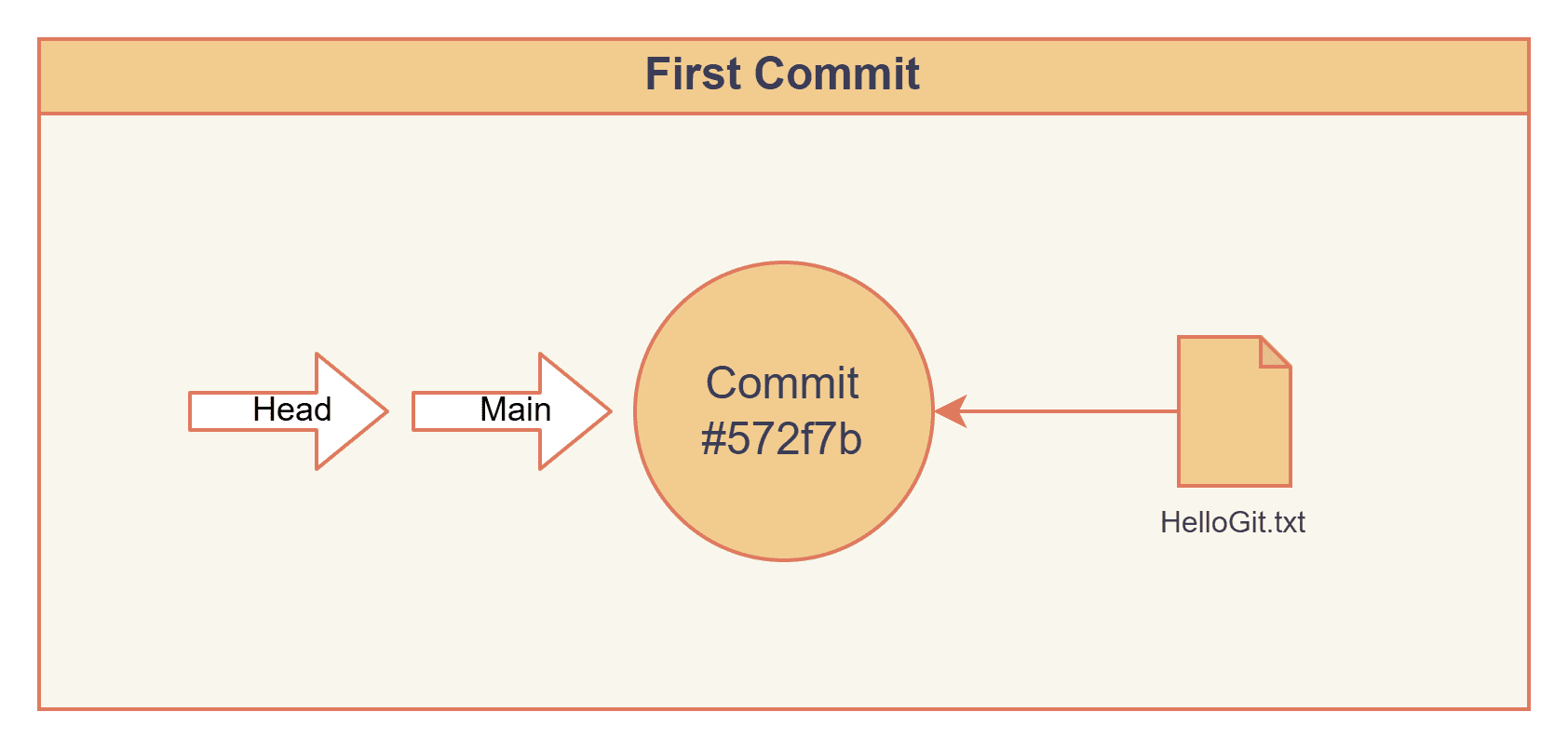

Our commit hash is 572f7b4c2808484e8078e09acccc073b810502f0. And our main branch pointer also contains this hash.

> cat .git/refs/heads/main

572f7b4c2808484e8078e09acccc073b810502f0

#572f7b is our first node of the tree, and the HEAD and main pointers are both pointing at it.

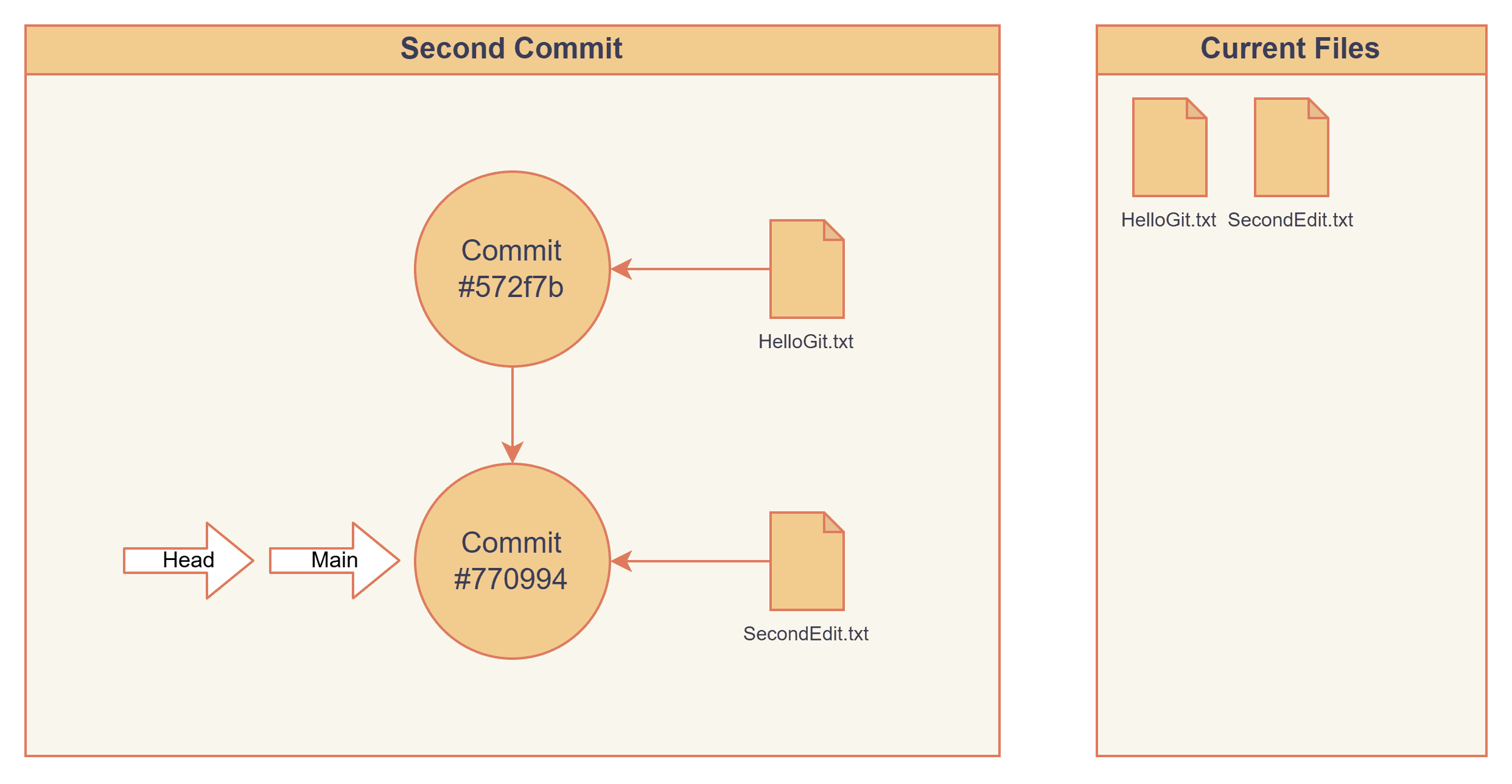

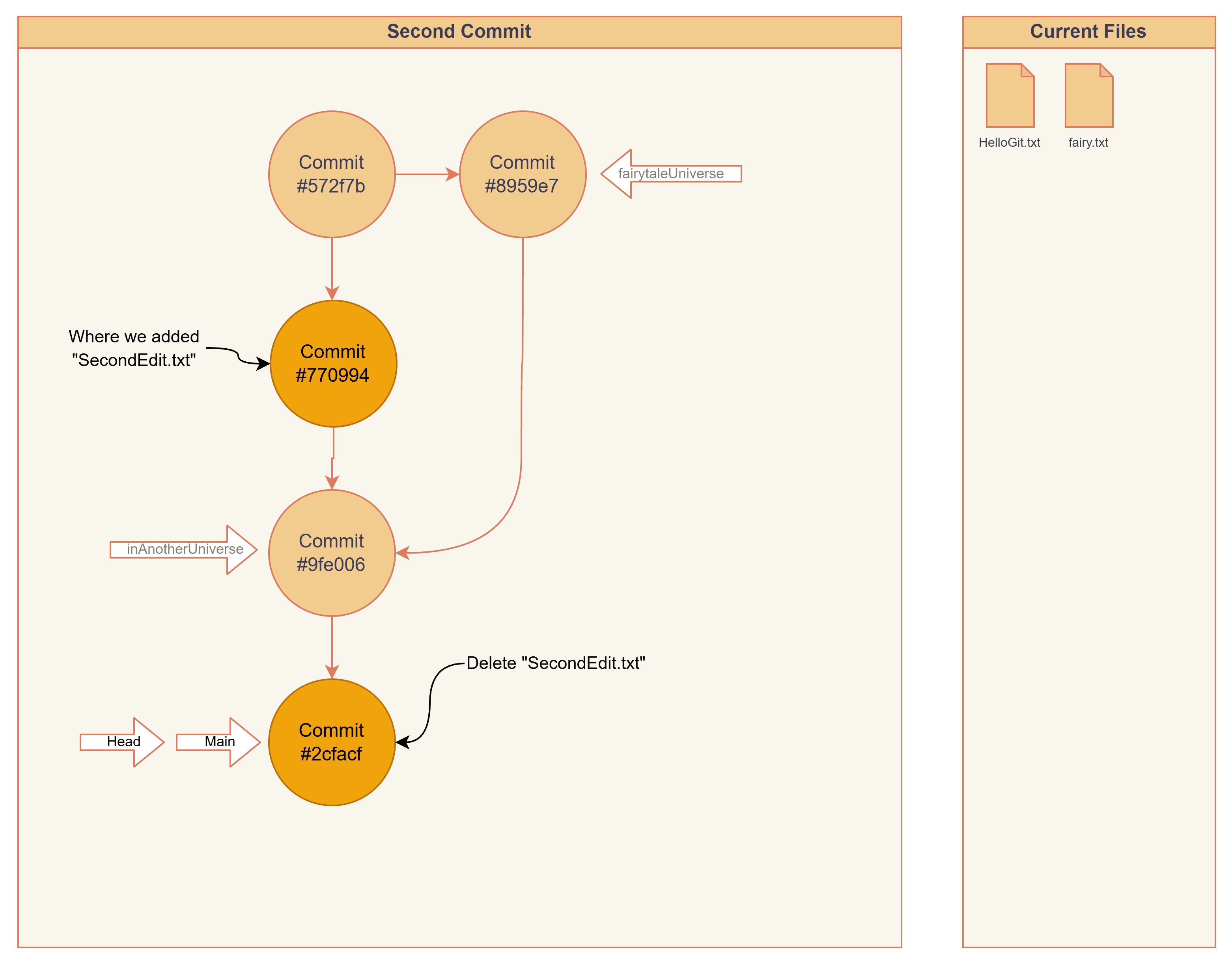

Now we create a second edit and commit to the main branch.

The HEAD and main pointers are pointing to our latest commit #770994.

Our folder contains HelloGit.txt and SecondEdit.txt.

> touch SecondEdit.txt

> git add SecondEdit.txt

> git commit

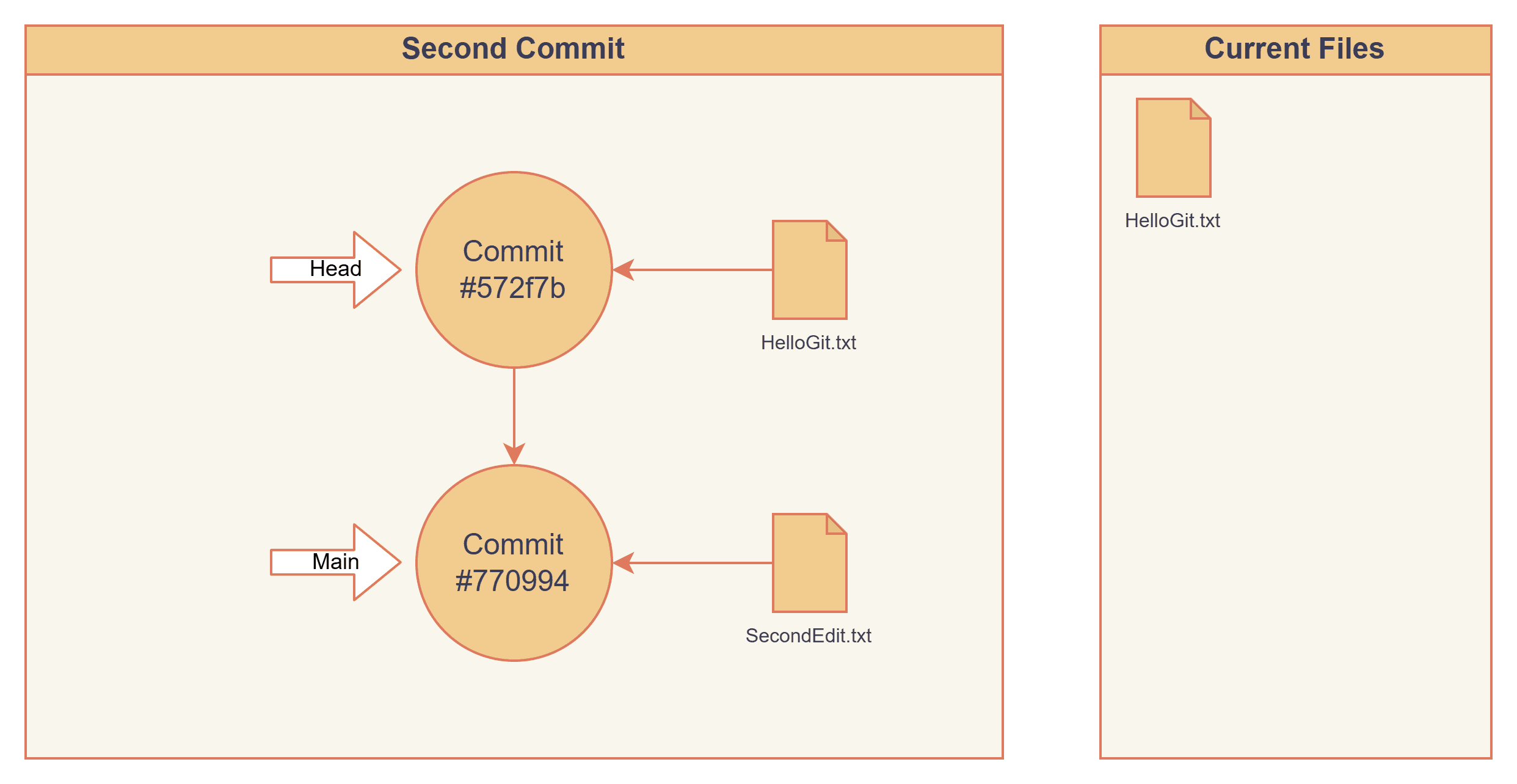

We can go back in time by checking out our first commit, #572f7b. This loads a snapshot of the project exactly as it existed at that moment. Only HelloGit.txt exists, and SecondEdit.txt is gone.

> git checkout 572f7

> cat .git/HEAD

572f7b4c2808484e8078e09acccc073b810502f0

> cat .git/refs/heads/main

770994fdbb67ece2f7aac1f3461b9f780652d30e

Branching

Let's try branching off from the main branch. Creating a new branch will create a pointer named "inAnotherUniverse", and nothing more than that, no snapshots, no copies, no new nodes.

"inAnotherUniverse" stores #770994, which points to the latest commit, also the same as the main branch, where we are branching off from.

> git checkout main

> git branch inAnotherUniverse

> ls .git/refs/heads/

inAnotherUniverse main

> cat .git/refs/heads/inAnotherUniverse

770994fdbb67ece2f7aac1f3461b9f780652d30e

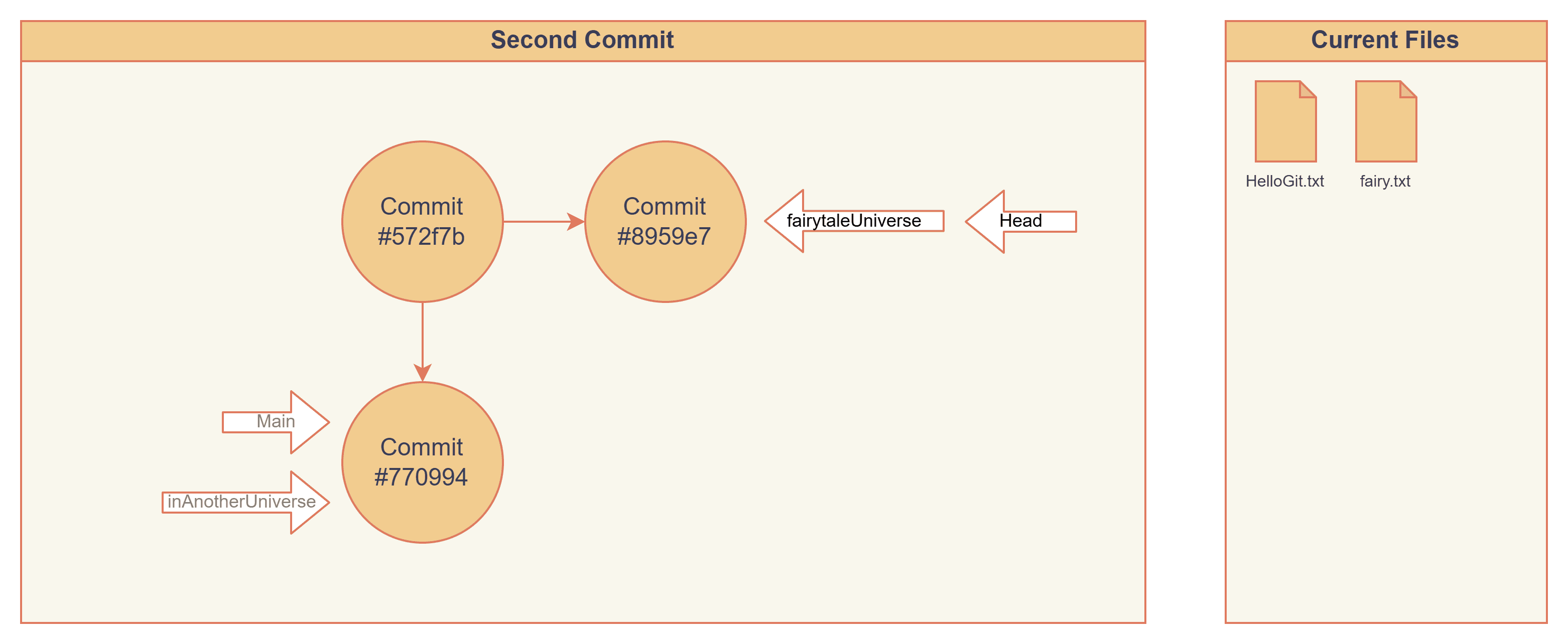

Actually, we can branch from any commit we want.

Actually, we can branch from any commit we want.

> git checkout 572f7b

> git branch fairytaleUniverse

> cat .git/refs/heads/fairytaleUniverse

572f7b4c2808484e8078e09acccc073b810502f0

Although we have created a branch,

Although we have created a branch, HEAD is still at commit #572f7b4 rather than fairytaleUniverse. We are currently in a detached HEAD state, meaning HEAD is not pointing to any branch. Commits made from this state are not referenced by any branch, but they are still recoverable via reflog for a while. If you don’t create a branch or tag for them, they may eventually be pruned by garbage collection based on your reflog/GC settings (the exact timing is configurable and varies by setup).

> git branch

* (HEAD detached at 572f7b4)

fairytaleUniverse

inAnotherUniverse

main

We can find all these branch pointers in .git/refs/heads, and all they store is just a commit hash.

> ls .git/refs/heads/

fairytaleUniverse inAnotherUniverse main

> cat .git/refs/heads/*

572f7b4c2808484e8078e09acccc073b810502f0

770994fdbb67ece2f7aac1f3461b9f780652d30e

770994fdbb67ece2f7aac1f3461b9f780652d30e

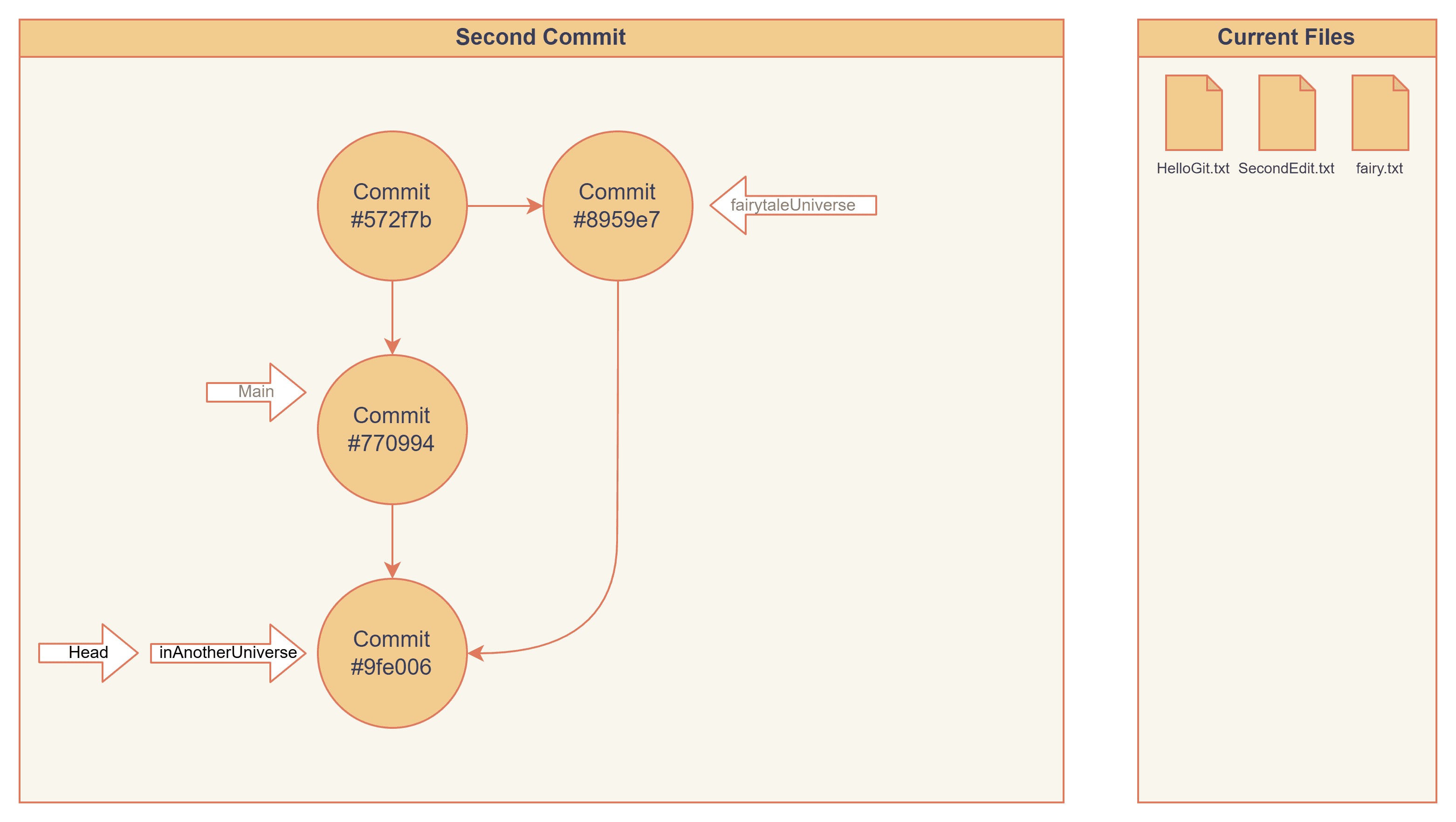

Now I create a commit on fairytaleUniverse, and at this moment, the tree branches out for real.

> git checkout fairytaleUniverse

> touch fairy.txt

> git add fairy.txt

> git commit

Merging

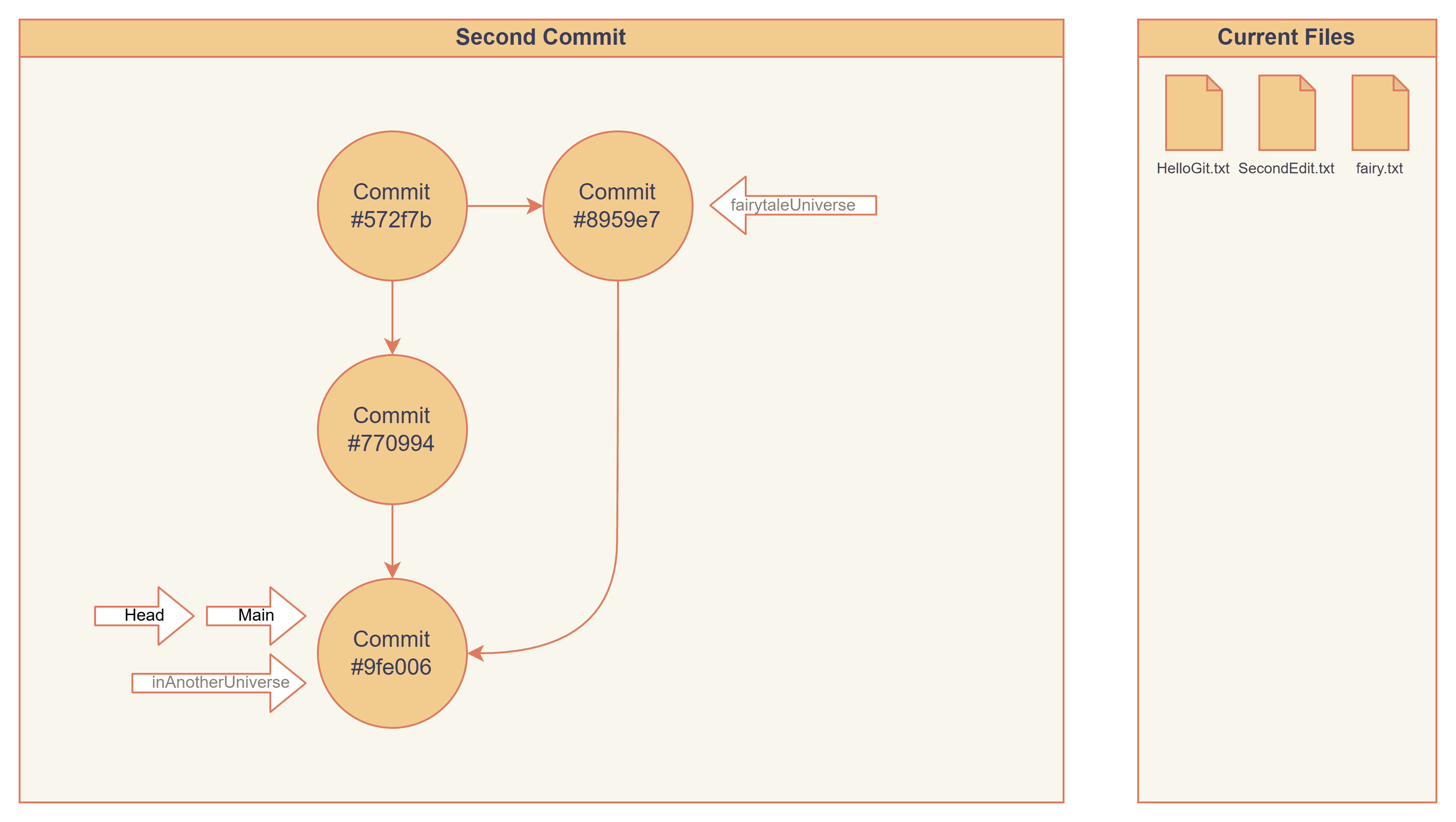

Let's finish our first section by merging fairytaleUniverse into inAnotherUniverse, and see what will happen. This will create a new commit 9fe006, and inAnotherUniverse now points at it.

> git checkout inAnotherUniverse

> git merge fairytaleUniverse

Now we are ahead of main. What if we merge inAnotherUniverse and main, will it create a new commit? It fast-forwards and does not create a new commit. It changes the main pointer from #770994 to #9fe006

> git merge main # Good practice: merge main into the sub-branch and resolve conflicts here.

Already up to date.

> git checkout main

> git merge inAnotherUniverse

Updating 770994f..9fe006a

Fast-forward

fairy.txt | 0

1 file changed, 0 insertions(+), 0 deletions(-)

create mode 100644 fairy.txt

Finally, let me introduce a very useful command git log --graph --reflog. This will show logs in Git visually. And we can use it to verify if the graphs I drew above are correct.

> git log --graph --reflog

* commit 9fe006ac0e277b191de7ec70f789ce60f8217bdd (HEAD -> main, inAnotherUniverse)

|\ Merge: 770994f 8959e7f

| | Author: don@winUbuntu <[email protected]m>

| | Date: Sat Jan 24 22:41:36 2026 -0700

| |

| | Merge branch 'fairytaleUniverse' into inAnotherUniverse

| |

| * commit 8959e7f103ab1aa5efda740ba15b70200e5fb1d2 (fairytaleUniverse)

| | Author: don@winUbuntu <[email protected]m>

| | Date: Sat Jan 24 22:25:31 2026 -0700

| |

| | Creating fairy

| |

* | commit 770994fdbb67ece2f7aac1f3461b9f780652d30e

|/ Author: don@winUbuntu <[email protected]m>

| Date: Sat Jan 24 03:38:51 2026 -0700

|

| This is second edit

|

* commit 572f7b4c2808484e8078e09acccc073b810502f0

Author: don@winUbuntu <[email protected]m>

Date: Sat Jan 24 03:24:25 2026 -0700

This is our first commit

How Git stores our files?

Git is a magical tool, allowing us to revisit any point in time in a blink. This is possible because Git stores a snapshot of the entire project every time we create a commit. But wouldn't saving the whole project each time consume an enormous amount of space? Let’s explore how Git efficiently saves our files.

Snapshots

Let's open up our latest commit #9fe006 and see what's inside. We can find this snapshot inside .git/objects/9f, file name e006ac0e277b191de7ec70f789ce60f8217bdd. The first two characters are the folder name, and the rest is the file name.

This is a binary file, and we can read its content with the git cat-file command.

If you are really interested in reading this file as-is, you may take a look at this section: [[#How to read an object]].

> git cat-file -p 9fe006ac0e277b191de7ec70f789ce60f8217bdd

tree 1adbed20c8b4756ceba562ecafe22677d1fcdf44

parent 770994fdbb67ece2f7aac1f3461b9f780652d30e

parent 8959e7f103ab1aa5efda740ba15b70200e5fb1d2

author don@winUbuntu <[email protected]m> 1769319696 -0700

committer don@winUbuntu <[email protected]m> 1769319696 -0700

Merge branch 'fairytaleUniverse' into inAnotherUniverse

This file stores details about this commit, such as its parents and who committed it. And there is a tree that we don't know what it is, let's git cat-file the tree object to look inside.

> git cat-file -p 1adbed20c8b4756ceba562ecafe22677d1fcdf44

100644 blob e69de29bb2d1d6434b8b29ae775ad8c2e48c5391 HelloGit.txt

100644 blob e69de29bb2d1d6434b8b29ae775ad8c2e48c5391 SecondEdit.txt

100644 blob e69de29bb2d1d6434b8b29ae775ad8c2e48c5391 fairy.txt

> git cat-file -p e69de29bb2d1d6434b8b29ae775ad8c2e48c539

# output nothing

We can see the filenames and their associated blob hashes. But why are the hashes identical? Git compresses file data into 'blobs' and generates a hash based on their content. If two files have identical content, they produce the same hash and are stored as a single blob to save space. Let's create another file with different content, and see what the difference is.

> echo beepbeep > robot.txt

> git add . && git commit

> git cat-file -p HEAD

tree ad3976dec6c9dff217ec0273d0b90c1adee433a1

parent 9fe006ac0e277b191de7ec70f789ce60f8217bdd

author don@winUbuntu <[email protected]m> 1769412519 -0700

committer don@winUbuntu <[email protected]m> 1769412519 -0700

adding robot

robot.txt has a different hash, and if we read this blob, we can see the content of robot.txt.

> git cat-file -p ad3976dec6c9dff217ec0273d0b90c1adee433a1

100644 blob e69de29bb2d1d6434b8b29ae775ad8c2e48c5391 HelloGit.txt

100644 blob e69de29bb2d1d6434b8b29ae775ad8c2e48c5391 SecondEdit.txt

100644 blob e69de29bb2d1d6434b8b29ae775ad8c2e48c5391 fairy.txt

100644 blob e608e561beb2bd1548a9368cd1d230ea1fd09ad7 robot.txt

> git cat-file -p e608e561beb2bd1548a9368cd1d230ea1fd09ad7

beepbeep

Git stores files with the same content in the same blob. Which means all unmodified files use the previous blob and the same hash to be stored. And only the modified files will be saved as a new blob.

Staging Area

Before we create a commit, Git save your work in three places:

- Working Directory: The files in your project folder that you can see and edit.

- Staging Area: The changes to include in the next commit.

- Stash Area: This is a temporary place to save unfinished changes.

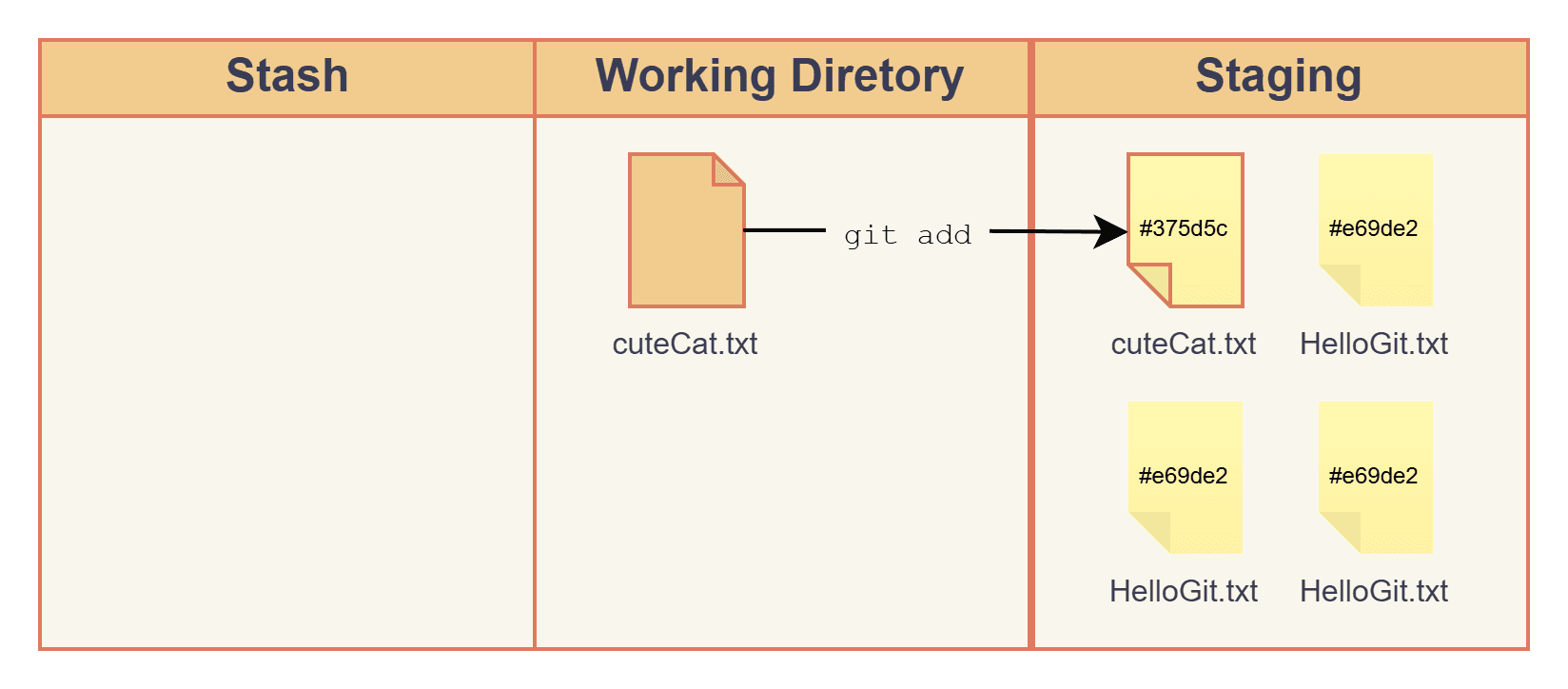

Here, I will show you what actually happened when you stage a file. We will use cuteCat.txt as an example.

First, we create cuteCat.txt, right now it is in the working directory. Then we run: git add cuteCat.txt. This stages cuteCat.txt, which will be included in the next commit.

> echo meow > cuteCat.txt

> git add cuteCat.txt

> git status

On branch main

Changes to be committed:

(use "git restore --staged <file>..." to unstage)

new file: cuteCat.txt

But what exactly does "staging" a file mean? There are actually two things happening:

- Create a blob for the changed file

- Update the staging area to include the hash of the changed file.

Creating blob for changed files

If we compare the .git/objects folder before and after git add, we can see that Git created a new file 5d5c3c... inside a new folder named 37.

> echo meow > cuteCat.txt

> ls .git/objects/ # Before git add

0d 12 1a 57 77 89 92 9f ad d7 e6 info pack

> git add cuteCat.txt

> ls .git/objects/ # After git add, new folder 37 is created

0d 12 1a 37 57 77 89 92 9f ad d7 e6 info pack

> ls .git/objects/37/

5d5c3ce54c13190b2be179e7f3717ebdfd5adf # the new object

And the new file contains, you guessed it: "meow". When we run git add, Git hashes the file contents and stores them as new blob objects.

> git cat-file -p 375d5c3ce54c13190b2be179e7f3717ebdfd5adf

meow

The actual "Staging Area"

The "staging area" is actually just a file .git/index saved as a binary in a specific binary. But if we open it up with a hex editor, we can still find our "cuteCat.txt" and its blob hash. The content is similar to git ls-files --stage.

> git ls-files --stage

100644 e69de29bb2d1d6434b8b29ae775ad8c2e48c5391 0 HelloGit.txt

100644 e69de29bb2d1d6434b8b29ae775ad8c2e48c5391 0 SecondEdit.txt

100644 375d5c3ce54c13190b2be179e7f3717ebdfd5adf 0 cuteCat.txt

100644 e69de29bb2d1d6434b8b29ae775ad8c2e48c5391 0 fairy.txt

Finally, let's verify our staging area is indeed a file that contains hashes of every file, like a tree object we see in a commit. We delete the index file and reset everything, and see what's in our staging area.

Finally, let's verify our staging area is indeed a file that contains hashes of every file, like a tree object we see in a commit. We delete the index file and reset everything, and see what's in our staging area.

> rm .git/index

> git reset HEAD --hard

HEAD is now at 9fe006a Merge branch 'fairytaleUniverse' into inAnotherUniverse

> git ls-files --stage

100644 e69de29bb2d1d6434b8b29ae775ad8c2e48c5391 0 HelloGit.txt

100644 e69de29bb2d1d6434b8b29ae775ad8c2e48c5391 0 SecondEdit.txt

100644 e69de29bb2d1d6434b8b29ae775ad8c2e48c5391 0 fairy.txt

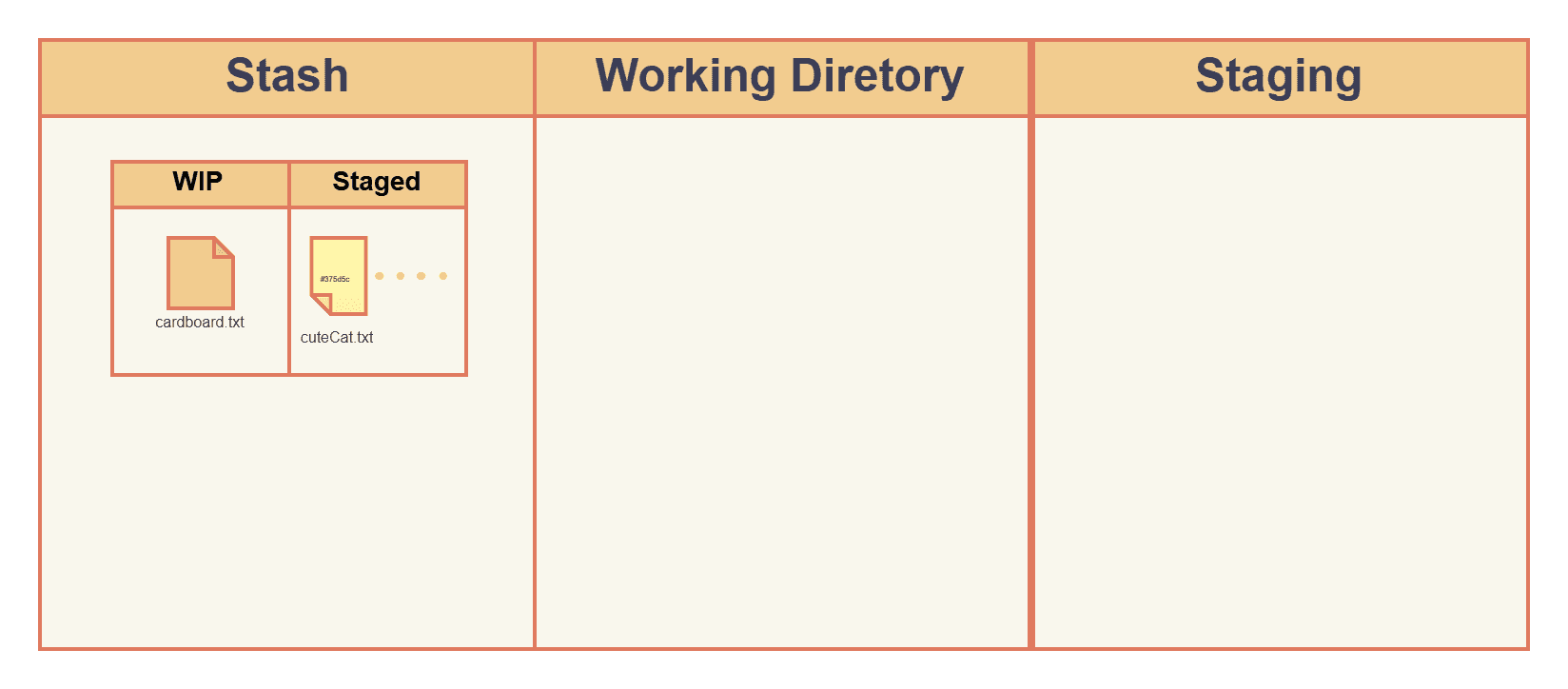

Stash

Stash is a place to temporarily hold your tracked files in the working directory and staged files, in a stack (LIFO) manner. Right now the cute cat is in the staging area, let's create a cardboard.txt in working tree and stash them as a demo:

> touch cardboard.txt

> git stash

Saved working directory and index state WIP on main: 9fe006a Merge branch 'fairytaleUniverse' into inAnotherUniverse

Wait... It did not stash cardboard.txt , it is still in our working directory.

> ls

HelloGit.txt SecondEdit.txt cardboard.txt fairy.txt

Well, git stash alone will only stash tracked files, where cardboard is untracked. Let's pop that stash and try that again:

> git stash pop

On branch main

Changes to be committed:

(use "git restore --staged <file>..." to unstage)

new file: cuteCat.txt

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

cardboard.txt

If we want to stash it, we need to add -u for newly created files, or -a for ignored files. Also, we can use -m to modify the message, so we can tell which stash we are looking for.

> git stash -a -m thisIsCardboard

Saved working directory and index state On main: thisIsCardboard

> git stash list

stash@{0}: On main: thisIsCardboard

Inside stash

Git stores the latest stash in .git/refs/stash, and the whole stash stack in .git/logs/refs/stash. I wonder how git stores our things inside... It is a Git commit object. We have seen #9fe006, but there are two parents we never heard of.

> cat .git/refs/stash

b517b6ea949220437e7363aff64e375ef51c4b7

> git cat-file -t b517b6ea949220437e7363aff64e375ef51c4b7

commit

> git cat-file -p b517b6ea949220437e7363aff64e375ef51c4b7

tree 9955efe051b5b8e9e0fc90f5e418625c64ccba5f

parent 9fe006ac0e277b191de7ec70f789ce60f8217bdd

parent 65d0d0cb1d36bb117549d3fe8c0f04f17c2d0e5e

parent 885682e9fb86eb9c7da63920ae44d7e1c860239f

author don@winUbuntu <[email protected]m> 1769834356 -0700

committer don@winUbuntu <[email protected]m> 1769834356 -0700

Let's crack them open and see what's inside. The first one has a message of "index on main", which is the staging area we just investigated, and the other file is "untracked files", which is our working directory. And from looking into their tree object, they are indeed what we are looking for.

> git cat-file -p 65d0d0cb1d36bb117549d3fe8c0f04f17c2d0e5e

tree 9955efe051b5b8e9e0fc90f5e418625c64ccba5f

parent 9fe006ac0e277b191de7ec70f789ce60f8217bdd

author don@winUbuntu <[email protected]m> 1769834356 -0700

committer don@winUbuntu <[email protected]m> 1769834356 -0700

index on main: 9fe006a Merge branch 'fairytaleUniverse' into inAnotherUniverse

> git cat-file -p 9955efe051b5b8e9e0fc90f5e418625c64ccba5f

100644 blob e69de29bb2d1d6434b8b29ae775ad8c2e48c5391 HelloGit.txt

100644 blob e69de29bb2d1d6434b8b29ae775ad8c2e48c5391 SecondEdit.txt

100644 blob 375d5c3ce54c13190b2be179e7f3717ebdfd5adf cuteCat.txt

100644 blob e69de29bb2d1d6434b8b29ae775ad8c2e48c5391 fairy.txt

> git cat-file -p 885682e9fb86eb9c7da63920ae44d7e1c860239f

tree bf81bb1e72f595d92b2c73a89f6a465052981560

author don@winUbuntu <[email protected]m> 1769834356 -0700

committer don@winUbuntu <[email protected]m> 1769834356 -0700

untracked files on main: 9fe006a Merge branch 'fairytaleUniverse' into inAnotherUniverse

> git cat-file -p bf81bb1e72f595d92b2c73a89f6a465052981560

100644 blob e69de29bb2d1d6434b8b29ae775ad8c2e48c5391 cardboard.txt

Default stash behavior

By default, git stash pop restores your working tree, but does not restore the changes that were originally staged.

To demonstrate, I make sure everything is clean by making a git reset. Put V1 "meow" into staging and V2 "nyan" into the working tree.

> git reset --hard HEAD

HEAD is now at 9fe006a Merge branch 'fairytaleUniverse' into inAnotherUniverse

> ls

HelloGit.txt SecondEdit.txt fairy.txt

> echo meow > cuteCat.txt

> git add cuteCat.txt

> echo nyan > cuteCat.txt

After stashing and popping, the staged V1 is replaced with V2:

> git stash

Saved working directory and index state WIP on main: 9fe006a Merge branch 'fairytaleUniverse' into inAnotherUniverse

> git stash pop

On branch main

Changes to be committed:

new file: cuteCat.txt

Dropped refs/stash@{0} (4cb6e8cc5cbeed3f951507854dab33f06cadc214)

> git diff --staged

diff --git a/cuteCat.txt b/cuteCat.txt

new file mode 100644

index 0000000..38805f6

--- /dev/null

+++ b/cuteCat.txt

@@ -0,0 +1 @@

+nyan

To make sure Git restores your files as-is, you can run git stash pop --index, and git will place them back in the original place. Git stores your working directory in the tree of the stash commit object, and the staged one in the parent (index) tree.

> git stash pop --index

On branch main

Changes to be committed:

new file: cuteCat.txt

Changes not staged for commit:

modified: cuteCat.txt

Dropped refs/stash@{0} (1f3f2d13e26fdd2fec6ff8e7f80164349229bb3d)

> git diff

diff --git a/cuteCat.txt b/cuteCat.txt

index 375d5c3..38805f6 100644

--- a/cuteCat.txt

+++ b/cuteCat.txt

@@ -1 +1 @@

-meow

+nyan

Summary

Git stash puts your working files and staged files into a temporary commit. And you can stash multiple times to save multiple "ongoing progress".

git stash: stash your work,-uto include untracked files,-mto modify message.- Latest stash stored at

.git/refs/stash, and the stash stack in.git/logs/refs/stash - A stash is a commit object and your data is stored in:

- tree: the working tree

- parent (staging index): staging area

- parent (untracked): files Git has never seen

git stash popwill drop your original staging changes, use--indexto preserve it.

Re..Re..Re..Re..

Reset, revert, restore, rebase. Am I the only one who gets confused? Or Git deserves some git blame for naming?

Reset

git reset sets our branch pointer to any specific commit, and allows us to wipe or bring files in our working tree and staged area.

git reset has three different options --soft, --mixed, and --hard, which allows us to keep unstaged files or staged files in different ways.

Let's see it in action:

Preparation

Here I put SecondEdit.txt on staging, and fairy.txt on working tree.

> git reset --hard HEAD # make sure everything is clean

> echo "at staging" > SecondEdit.txt

> git add SecondEdit.txt

> echo "at working tree" > fairy.txt

> git status

On branch main

Changes to be committed:

modified: SecondEdit.txt

Changes not staged for commit:

modified: fairy.txt

I stash the current state. We restore this stash without deleting it using git stash apply

> git stash

Saved working directory and index state WIP on main: 9fe006a Merge branch 'fairytaleUniverse' into inAnotherUniverse

> git stash apply --index # This stash will not be removed.

On branch main

Changes to be committed:

modified: SecondEdit.txt

Changes not staged for commit:

modified: fairy.txt

Reset to current base commit

--soft will keep both staged and unstaged changes, only moving the branch pointer, in this case, it resets nothing.

> git reset --soft HEAD

> git status

On branch main

Changes to be committed:

modified: SecondEdit.txt

Changes not staged for commit:

modified: fairy.txt

--mixed reset our staging area (index). Note both files are updated in working directory, so they are now both not staged.

> git reset --mixed HEAD

Unstaged changes after reset:

M SecondEdit.txt

M fairy.txt

> git status

On branch main

Changes not staged for commit:

modified: SecondEdit.txt

modified: fairy.txt

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

Here I restore our initial state before trying --hard option.

> git reset --hard HEAD

> git stash apply --index

--hard will wipe both working directory and staging area.

> git reset --hard HEAD

HEAD is now at 9fe006a Merge branch 'fairytaleUniverse' into inAnotherUniverse

> git status

On branch main

nothing to commit, working tree clean

Reset to previous commit

Now we try to do the same and see if we can bring staging area and working directory to previous commit.

Then we run git reset --soft. This keeps both "staging area" and "working tree" unchanged. Since fairy.txt is in the staging area (index) we kept, it is now in the staging area as a new file.

# skipped the part I reset everything

> git reset --soft HEAD~1

# We are back to previous commit #770994

> git show

commit 770994fdbb67ece2f7aac1f3461b9f780652d30e (HEAD -> main)

[truncated]...

> git status

On branch main

Changes to be committed:

modified: SecondEdit.txt

new file: fairy.txt

Changes not staged for commit:

modified: fairy.txt

> git show :fairy.txt # empty

Next is --mixed, which will wipe the staging area, only retaining the working directory.

# skipped the part I reset everything, including going back to 9fe006a

> git reset HEAD~1 #mixed is the default option

> git status

On branch main

Changes not staged for commit:

modified: SecondEdit.txt

Untracked files:

fairy.txt # Not in index, therefore untracked

And finally --hard, and it wipes everything.

# skipped the part I reset everything, including going back to 9fe006a

> git reset --hard HEAD~1

HEAD is now at 770994f This is second edit

> git status

On branch main

nothing to commit, working tree clean

To read more on how HEAD~1 works, take a look at [[#More on HEAD pointer]].

Reset to anywhere

git reset simply changes the pointer of the current branch; we can change it to anywhere we want, not only where we have been.

> git checkout 572f7b

> touch ghost.txt

> git add .

> git commit

# Now our HEAD is at detached state,

# and we branch off from 572f7b with no branch name.

> git checkout main

> git reset d74b3a

Now our main branch points to the ghost commit. We can visualize it by running git log. I hope this further clarifies that branches are just a label, and we store all our work in the whole git family tree, not the "main branch".

Now our main branch points to the ghost commit. We can visualize it by running git log. I hope this further clarifies that branches are just a label, and we store all our work in the whole git family tree, not the "main branch".

> git log --graph --reflog

* commit d74b3a4cbf9c535951b5bd7d3aede71d43bc98c8 (HEAD -> main)

| Author: don@winUbuntu <[email protected]m>

| Date: Sun Jan 25 19:39:46 2026 -0700

|

| ghost is created

|

| * commit 9fe006ac0e277b191de7ec70f789ce60f8217bdd (inAnotherUniverse)

|/| Merge: 770994f 8959e7f

| | Author: don@winUbuntu <[email protected]m>

| | Date: Sat Jan 24 22:41:36 2026 -0700

| |

| | Merge branch 'fairytaleUniverse' into inAnotherUniverse

| |

| * commit 8959e7f103ab1aa5efda740ba15b70200e5fb1d2 (fairytaleUniverse)

| | Author: don@winUbuntu <[email protected]m>

| | Date: Sat Jan 24 22:25:31 2026 -0700

| |

| | Creating fairy

| |

* | commit 770994fdbb67ece2f7aac1f3461b9f780652d30e

|/ Author: don@winUbuntu <[email protected]m>

| Date: Sat Jan 24 03:38:51 2026 -0700

|

| This is second edit

|

* commit 572f7b4c2808484e8078e09acccc073b810502f0

Author: don@winUbuntu <[email protected]m>

Date: Sat Jan 24 03:24:25 2026 -0700

This is our first commit

Summary

git resetmoves our branch pointer. And keep/wipe staging and working directory accordingly.- We can reset our branch to any commit we want, even branches we have never reached before.

| Mode | Wipe Staging Area? | Wipe Working Directory? | Wipe untracked? |

|---|---|---|---|

| --soft | No | No | No |

| --mixed (default) | Yes | No | No |

| --hard | Yes | Yes | No |

Revert

Revert won’t touch old commits. It adds a new commit that undoes a commit. If something was added, it gets removed; if something was removed, it comes back. Revert is best for:

- Reverting old commits

- Reverting for a reason, for record.

- For safety, when you are not certain.

Reverting a simple commit

Here we try to revert the commit #770994, where we added the file SecondEdit.txt

> git revert 770994

[main 2cfacff] Revert "This is second edit"

1 file changed, 0 insertions(+), 0 deletions(-)

delete mode 100644 SecondEdit.txt

> git show

commit 2cfacffedfa3aca2fe7ce5e7fb1ef75b91df5be9 (HEAD -> main)

Author: don@winUbuntu <[email protected]m>

Date: Sat Jan 31 14:48:49 2026 -0700

Revert "This is second edit"

This reverts commit 770994fdbb67ece2f7aac1f3461b9f780652d30e.

diff --git a/SecondEdit.txt b/SecondEdit.txt

deleted file mode 100644

index e69de29..0000000

Reverting a merge

Reverting a merge is a bit different; here we try to revert #9fe006, and it failed.

> git reset --hard HEAD~1 # back to #9fe006 for clean demo

> git revert HEAD

error: commit 9fe006ac0e277b191de7ec70f789ce60f8217bdd is a merge but no -m option was given.

fatal: revert failed

We need to provide which branch we want to revert to, using the -m parameter followed by parent number. Here we choose our first parent (770994) as our main branch.

> git revert -m 1 HEAD # revert to the first parent.

[main ae10c9e] Revert "Merge branch 'fairytaleUniverse' into inAnotherUniverse"

1 file changed, 0 insertions(+), 0 deletions(-)

delete mode 100644 fairy.txt

As a result,

As a result, fairy.txt is removed. Later, if I try to merge that branch back in:

> git merge 8959e7

Already up to date.

Git tells us we are already up to date because the merge history is preserved. Reverting a merge commit will invert the changes, not the merge itself, which is why Git thinks the branch is already merged if you try to merge it again later.

Restore

git restore is Git's "newer" way to bring a file from a specific commit (default HEAD). This is to replace the double-duty git checkout command, and handle the "restoring files" function. All git restore does is "copy a file from a specific commit, and paste it to the working tree or the staging area".

Preparation

Here I put SecondEdit.txt on staging, and fairy.txt on working tree, just like what we did in [[#Reset]].

> git reset --hard 9fe006

HEAD is now at 9fe006a Merge branch 'fairytaleUniverse' into inAnotherUniverse

> git stash apply --index

On branch main

Changes to be committed:

(use "git restore --staged <file>..." to unstage)

modified: SecondEdit.txt

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git restore <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: fairy.txt

Restoring from current commit

Well, honestly Git already states it clearly. We unstaged using --staged, and plain git restore to discard changes. But let's see it in action.

Here we unstaged SecondEdit.txt from index. This copies the base commit's SecondEdit.txt into staging area.

> git restore --staged SecondEdit.txt

> git status

On branch main

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git restore <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: SecondEdit.txt

modified: fairy.txt

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

What about the file in current working directory, will it be replaced? The working directory remains the same. This shows we are not copying the staged file into working directory, we are copying the base commit's file into staging area only. The staged version will be overwritten.

# I reset everything again.

> echo 'at working directory' > SecondEdit.txt

> cat SecondEdit.txt

at working directory

# This is the content of "SecondEdit.txt" in working directory

> git show :SecondEdit.txt

at staging

# This is the content of "SecondEdit.txt" in staging area

> git stash

> git stash pop

> cat SecondEdit.txt

at working directory

> git show :SecondEdit.txt

# empty

The plain restore will restore files from the staging area to working directory. Now we put different content in SecondEdit.txt at different area, and see which version git restore will copy from.

> git reset --hard 9fe006

> cat SecondEdit.txt

# empty at base commit

> git stash apply --index

> echo 'at working directory' > SecondEdit.txt

# Base commit -> ""

# Staging Area -> "at staging"

# Working Directory -> "at working directory"

git restore <file> will copy files from staging area and replace the working directory file.

> git restore SecondEdit.txt

> cat SecondEdit.txt

at staging

To restore everything to HEAD, we can either run --staged and plain two times, or:

> git restore --staged --worktree SecondEdit.txt #worktree is the default option

> cat SecondEdit.txt

> #empty

Restoring from another commit

Remember in [[#Snapshots]], we create robot.txt? I want to bring it to here. We can find our lost robot.txt using --reflog; its commit hash is 0d6579

> git log --oneline --reflog

ae10c9e Revert "Merge branch 'fairytaleUniverse' into inAnotherUniverse"

2cfacff Revert "This is second edit"

60fecf8 (refs/stash) WIP on main: 9fe006a Merge branch 'fairytaleUniverse' into inAnotherUniverse

31b73fe index on main: 9fe006a Merge branch 'fairytaleUniverse' into inAnotherUniverse

0d6579d adding robot # This is what we are looking for

d74b3a4 ghost is created

9fe006a (HEAD -> main, inAnotherUniverse) Merge branch 'fairytaleUniverse' into inAnotherUniverse

8959e7f (fairytaleUniverse) Creating fairy

770994f This is second edit

572f7b4 This is our first commit

Now, we can use git restore to bring the robot back from a dangling commit.

> git reset --hard 9fe006

> git restore --source=0d6579 robot.txt

> cat robot.txt

beepbeep

Summary

git reset moves a branch pointer.

| Mode | Wipe Staging Area? | Wipe Working Directory? | Wipe untracked? |

|---|---|---|---|

| --soft | No | No | No |

| --mixed (default) | Yes | No | No |

| --hard | Yes | Yes | No |

git revert does the opposite of a commit.

- You need to specify a parent using

-mwhile reverting a merge. - You undo the changes, not the merge. The merge still exists, therefore you cannot merge it again, not the easy way.

git restore copies files from a specific commit.

--staged: copy from base commit to staging area (index).--worktree(default): copy from staging area to working area.--staged --worktree: do both, copy base commit to staging area and working area.--source=<hash>: choose the source to restore from.

Rebase

Rebase is another method to combine two branches. In [[#Merging]], we merged the main branch and the fairytale branch. Now let's combine the same two branches using rebase.

Basic

Here we rebase our fairytale #8959e7 onto #770994. It creates a new commit d047 with the message "Creating fairy" (same as 8959e7). What Git does is, starting from #770994, redo the commits of the fairytale branch (8959e7). Since

> git switch main # git switch is just git checkout with another name

Already on 'main'

> git reset --hard HEAD~1

HEAD is now at 770994f This is second edit

> git switch fairytaleUniverse

Switched to branch 'fairytaleUniverse'

> git rebase main

Successfully rebased and updated refs/heads/fairytaleUniverse.

> git log --oneline

d047347 (HEAD -> fairytaleUniverse) Creating fairy

770994f (main) This is second edit

572f7b4 This is our first commit

This is the content of

This is the content of #d04734, the only difference from 8959e7 is that the parent changed from #572f7b... to #770994.... Which is exactly what rebase does, transplanting commit onto another parent. And because the content of the commit changed (the parent), the hash also changed.

> git cat-file -p d04734

tree 1adbed20c8b4756ceba562ecafe22677d1fcdf44

parent 770994fdbb67ece2f7aac1f3461b9f780652d30e

author don@winUbuntu <[email protected]m> 1769318731 -0700

committer don@winUbuntu <[email protected]m> 1770000932 -0700

Creating fairy

Patch-id

But then I wonder, is there anything stopping us from rebasing #8959e7 on main multiple times? I mean, there is no record of its original commit.

Even though the commit hashes are different, the actual changes are identical. Git can detect this by comparing their patch ID, a hash computed from the content of the changes. So even if the commit hashes and commit messages differ, Git can still recognize that the commits represent the same change.

> git rebase 8959e7

warning: skipped previously applied commit d047347

# Git knows we submitted this before

> git show 8959e7 | git patch-id

c1c228d6e9cee776018113a09f771347d6d434b4 8959e7f103ab1aa5efda740ba15b70200e5fb1d2

> git show d04734 | git patch-id

c1c228d6e9cee776018113a09f771347d6d434b4 d047347c67574a7f5f830203bdc5da6a00cbaf29

After combining all changes, we can point main to the latest commit #d04734. We merge fairytaleUniverse into main, this will not create a merge commit, as it will only fast forward.

> git switch main

Switched to branch 'main'

> git merge fairytaleUniverse

Updating 770994f..d047347

Fast-forward

fairy.txt | 0

1 file changed, 0 insertions(+), 0 deletions(-)

create mode 100644 fairy.txt

Most important

Do not rebase commits that exist outside your repository and that people may have based work on. If you follow that guideline, you’ll be fine. If you don’t, people will hate you, and you’ll be scorned by friends and family. -- From the official Git tutorial

Appendix

Lies that I made

-

Git is a DAG, not a family tree.

A family tree is inaccurate because: Commits can have one, two, more than two parents, and you can merge any two commits together, even two commits in the same history. A DAG means:

- Directed: It has one direction, children cannot point at parents.

- Acyclic: There are no loops.

- Graph: Like a tree, but allows more interconnections like merging multiple commits together.

-

I did not mention the remote part.

I decided not to include the concepts of remote, push, and pull here because I want to focus on the internal mechanism of Git rather than on how to use it as a tool. However, these features are still an important part of Git, and learning how to collaborate with other developers is also essential.

For example, writing structured and clean commit messages is an important practice when using Git. You may want to check out [https://www.conventionalcommits.org/zh-hant/v1.0.0/] if you would like to learn more.

-

I did not touch on conflicts.

Again, I want to focus on the internal git mechanism, not how to use git. It will make this already lengthy article even more unreadable. Maybe I will add another post for them in the future.

How to read an object

We can use a Python library zlib to read its content of this commit object. Here is a demo of reading the commit #9fe006. Our file is e006ac0e277b191de7ec70f789ce60f8217bdd inside the 9f folder.

[truncated]\.git\objects\9f>python3 # we run python in REPL for demo

>>> import zlib

>>> file = 'e006ac0e277b191de7ec70f789ce60f8217bdd'

>>> file_content = open(file, 'rb').read()

>>> file_content_decompressed = zlib.decompress(file_content)

>>> file_content_decompressed

b"commit 328\x00tree 1adbed20c8b4756ceba562ecafe22677d1fcdf44\nparent 770994fdbb67ece2f7aac1f3461b9f780652d30e\nparent 8959e7f103ab1aa5efda740ba15b70200e5fb1d2\nauthor don@winUbuntu <[email protected]> 1769319696 -0700\ncommitter don@winUbuntu <[email protected]> 1769319696 -0700\n\nMerge branch 'fairytaleUniverse' into inAnotherUniverse\n"

>>> len(file_content_decompressed)

339

It is the same as what we get from git cat-file, except the object type is missing.

we can use git cat-file -t 9fe006a to check the filetype of an object too.

commit #filetype

328 # 328 Bytes following the header

\x00 # a null byte, separate the header and content

tree 1adbed20c8b4756ceba562ecafe22677d1fcdf44\n

parent 770994fdbb67ece2f7aac1f3461b9f780652d30e\n

parent 8959e7f103ab1aa5efda740ba15b70200e5fb1d2\n

author don@winUbuntu <[email protected]m> 1769319696 -0700\n

committer don@winUbuntu <[email protected]m> 1769319696 -0700\n

\n

Merge branch 'fairytaleUniverse' into inAnotherUniverse\n

More on HEAD pointer

What does git reset HEAD~1 do?

Some say git reset HEAD~1 is the "undo" button for your latest commit. But what is the latest commit? If I am working on my branch and someone commits, will I reset their commit?

A more precise answer would be: it moves my current branch pointer to HEAD~1. And since HEAD points to where we are, we roll back by 1 commit. If we are on the main branch, HEAD~1 points to 770994. And if we are on fairytaleUniverse, HEAD~1 points to 572f7b

> git checkout main

> git rev-parse HEAD

9fe006ac0e277b191de7ec70f789ce60f8217bdd

> git rev-parse HEAD~1

770994fdbb67ece2f7aac1f3461b9f780652d30e

> git rev-parse HEAD~2

572f7b4c2808484e8078e09acccc073b810502f0

> git checkout fairytaleUniverse

> git rev-parse HEAD

8959e7f103ab1aa5efda740ba15b70200e5fb1d2

> git rev-parse HEAD~1

572f7b4c2808484e8078e09acccc073b810502f0

What if we got two parents?

HEAD~1 selects the first parent, which is the branch you were on when the merge was run. We can move between parents using

What if we got two parents?

HEAD~1 selects the first parent, which is the branch you were on when the merge was run. We can move between parents using HEAD^n.

> git checkout 9fe006

> git rev-parse HEAD

9fe006ac0e277b191de7ec70f789ce60f8217bd

> git rev-parse HEAD~1

770994fdbb67ece2f7aac1f3461b9f780652d30

> git rev-parse HEAD^1

770994fdbb67ece2f7aac1f3461b9f780652d30e

> git rev-parse HEAD^2

8959e7f103ab1aa5efda740ba15b70200e5fb1d2